OPINION: Norwegian Offshore Wind - great ambitions and advantages alongside challenges

By SIMON MARKUSSEN - Senior Underwriter

Norway has a strong maritime heritage, as well as substantial offshore territories with considerable wind-resources.

Its location within the European continent also makes development of offshore wind in Norway not only important for domestic use but also highly significant for the energy transition of its neighbours further south. Today, Norway has one of the highest per capita consumptions of energy in the world, with 25.8MWh per capita in 2022. This is largely due to energy-intensive industries as well as the high use of electricity for the heating of buildings[1].

The majority of Norwegian energy production today is Hydropower. However, by 2050 it is expected that the installed capacity of offshore wind will approximately match that of Hydropower. It is expected that, in 2050, two-thirds of Norwegian installed offshore wind will be floating at around 29GW, including 4GW for off-grid capacity for hydrogen production. The Norwegian floating wind installed capacity in 2050 is not far off the current installed offshore wind capacity outside of China. This is a substantial pipeline.

Figure 1 DNV - ENERGY TRANSITION NORWAY 2023, Table 3.1

Energy Transition Norway Norsk Industri Figure 1 DNV - ENERGY TRANSITION NORWAY 2023, Table 3.1

energy-transition-norway-2023.pdf (norskindustri.no)

Today, offshore wind in Norway is limited to the two demonstrators Unitech Zefyros and Tetraspar at 2.3MW and 3.6MW respectively, as well as the Hywind Tampen farm with 11 8MW units totaling 88MW. Thus, the total offshore wind capacity in Norway is about one-third of the size of the average operational German or UK Windfarm (~300MW), and much less than any commercial windfarm under construction in European waters.

The Hywind Tampen project was a significant infrastructure project on the west-coast of Norway, utilizing Norwegian contractors, facilities and infrastructure that has, until now, been primarily used by the Oil and Gas industry. The large Norwegian services industry that since the 1970s has been supporting the development and operation of Oil and Gas facilities in Norwegian and international waters is very well suited to support the advent of floating wind.

Norway has existing and easily modified locations for the assembly and integration of up-coming projects, perhaps especially for floating wind. These often have accommodated oil and gas assets which demand heavy-lift capabilities as well as significant draft. For some of these, available space needs to be extended – however, in sparsely populated Norway, this could be less of a challenge than in other countries.

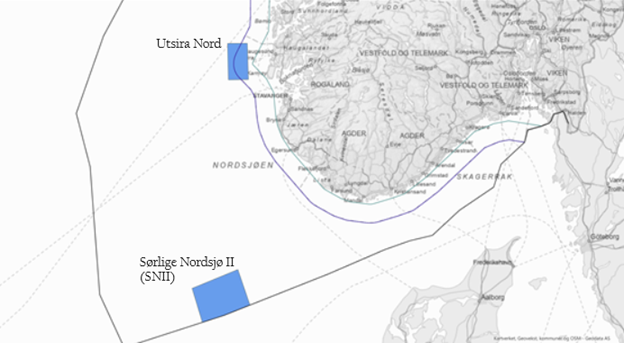

In the immediate pipeline for an award from the government is the Sørlige Nordsjø II (SNII), an area opened for 3GW of capacity. The government’s award for this area is to be split into two phases: the first phase for this area will be awarded with a requirement to build minimum 1400MW and maximum 1500MW. The site has a water depth of 53-70m and “among the best wind resources in the world”[2]. This, however, means that the project will be in very deep waters for a bottom-fixed project, although there are examples of other projects in deep waters, such as the Seagreen project in Scotland.

The project will be some 140km from Norwegian shores but some 200km from the appointed Norwegian grid connection point. The Norwegian grid connection from Norwegian TSO, Statnett, will be from point of connection, recommended as Kvinesdal outside of Kristiansand in Norway. This means that the building and operation of the offshore substation, export cable and onshore substation is do be done by whoever is awarded the project. Still, Statnett notes that it may take over the offshore grid connection responsibilities in the longer term under certain circumstances.

[2] Equinor, RWE and Hydro team up for offshore wind in the Norwegian North Sea - equinor.com

Figure 2 SNII and Utsira Nord, MAP: Kartverket/Geodata AS - Regjeringen.no

Sørlige Nordsjø II - regjeringen.no

The application deadline for SNII phase one lapsed in November. The process for SNII is to be a reversed auction, where those who are prequalified are to bid the lowest price at which they are willing to proceed with the project. There were seven applicants, a lower number than expected and desired by the government. The application process of the government stipulated that it was to prequalify a minimum of six and maximum of eight applicants.

The challenge now is that of the seven applicants, it is somewhat doubtful that two of these, Hydroelectric Corporation and Mingyang Smart Energy, will achieve some of the qualification criteria. This leaves the government with the challenge of potentially having fewer applicants than the lower limit they imposed themselves. Still, the remaining applicants are impressive consortiums with a mix of a Norwegian and international component.

The tentative auction date for SNII is February 2024 for those applicants who are prequalified, assuming they are of an adequate number for the process to be completed.

Figure 3 Overview of bidding consortiums for SNII and Utsira Nord

The other imminent process in Norway is the award of Utsira Nord. Located nearshore outside the Utsira Island outside Haugesund on the West-Coast of Norway, the average water depth at the location is 265m. This is quite deep compared to other existing floating projects, the threshold for floating wind often starting at around 60 meters, however, Utsira Nord water depths are comparable to those of Hywind Tampen.

Figure 4 Regjeringen.no - https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/energi/landingssider/havvind/utsira-nord/id2967232/

The Utsira area will be split into three areas, to have a minimum of 460MW and maximum 500MW each. In contrast to the SNII auction, this is an auction which includes price in its initial evaluation.

The applicants will be evaluated for fulfillment of criteria for adequate technical competence, financial strength as well as HSE related requirements. Those who qualify from these will be evaluated according to the following qualitative criteria:

Cost level 2030 (30%)

Innovation and technology development (20%)

Execution capability (30%)

Sustainability (10%)

Local impact (10%)

The applicant with the highest score will be able to choose a project area first, then subsequently the runner up chooses and then the third place gets the remaining area. Notably, the two largest areas will be able to increase the capacity of their areas to 750MW, if they are able to execute this within the same area of the project area.

This means that the Utsira Nord area is likely to have a capacity of 1.5-2GW.

There are good examples of strong consortiums stating they plan to bid for the project. As an example of preparedness of the industry, Equinor has already committed to using the Wergeland base, and the SPAR concept if they are to be awarded one of the Utsira areas. In a similar manner to what was done for Hywind Tampen, with the major difference being that likely now also foundation fabrication needs to be done there.

Assuming a first or second award to Equinor, and them opting to increase the size of the farm to 750MW, this would mean about 40-50 units, depending on the size of turbine chosen. This is about 4-5 times the number of units that the 11x8MW Hywind Tampen project.

The industry is responding to such commitments; Wergeland, for example, has been preparing plans to have a permanently installed crane at the location suitable for FOW integration[3]. Additionally, the port facilities are currently awaiting confirmation from the government to proceed with an 18MW GE demonstrator on the quayside of the base[4].

[3] Wergeland and PSW to extend port capacity with Huisman Quayside Crane (huismanequipment.com)

Other interesting applicants include Norsea Group, Parkwind and CIP. Norsea Group owns most of the oil and gas support bases along the Norwegian coast, as well as having recently purchased a quarry, Jelsa, well suited for the assembly and integration of FOW[5].

Norwegian industry is well suited to take on several aspects of the floating wind scene, with the notable and important part being turbine OEMs.

However, for Utsira Nord there are also challenges; for example, Ørsted recently announced it was withdrawing from the very prominent Blåvinge consortium.

Also, there have been significant delays in the Utsira Nord submission due date. From the original 1st of September to 1st of November, then to 15th November and then to be currently (as of 15th December 2023) defined as “the department will revert with updated application deadline” on the application website. There were also some delays for SNII, but there the application was accepted the 15th of November.

The reason for the delays are stated to be challenges in notifying, and getting acceptance from, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA)’s control organization EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA). This acceptance is needed for the significant governmental support the projects will need.

In the intermediate term, Norway also has potential for offshore wind being utilized to reduce CO2 emissions from its offshore oil and gas production. About one quarter of the CO2 emissions in Norway are from the oil and gas industry[6]. These oil and gas emissions are predominantly from gas-turbines energizing offshore oil and gas installations. There is therefore a big drive to electrify the offshore oil and gas installations in Norway.

There has been a high degree of focus on electrification of these units with powers from land, utilizing historical abundant, and cheap, Norwegian hydro-electricity. However, in recent years power prices have massively shifted and - as such – there is a lot more focus by the general public on using electricity from shore for electrification of oil and gas.

This creates the possibility of other measures to produce green electricity for oil and gas production facilities. This is the intention of the Hywind Tampen project. The project is not connected to the Norwegian grid but is rather connected to the oil and gas fields Snorre and Gullfaks. The project is expected to be able to provide 35% of the electrical needs of these[7].

Another example, of “wind for oil” is the Goliatvind project, where Source Galileo, Kansai Electric Power Company and Odfjell Oceanwind are collaborating with Vår Energi (O&G major ENI in Norway) to build five 15MW floating units totaling 75MW to support the Goilat SPAR type FPSO with renewable energy. The project will be in water depths of 3-400 meters. The Goilat FPSO is today electrified through a 75MW cable from shore. This cable can also be used for export of power from the floating project[8].

[5] NorSea - Vi forenkler (norseagroup.com)

[7] Startskuddet har gått for Norges havvindeventyr - Equinor

[8] Demonstrasjon av flytende havvindteknologi i Norge | GoliatVind

Odfjell OceanWind is a company owned by Odfjell Drilling, a globally renowned owner and operator of semi-submersible drilling rigs for the oil and gas industry specialized for operation in harsh conditions. This gives them a strong foundation for developing foundations for floating wind.

There are massive ambitions for offshore wind in Norway. The strong wind-resources and existing industries should be able to support a strong industry. However, the Norwegian government needs to be prompt in its issuance of new areas, as well as completion of existing processes. The role of the Norwegian TSO will also be interesting, as it is generally expected that they will aim at more of a Dutch and French model rather than a British approach.

In all, it will be exciting to see the outcomes of both ongoing auctions in Norwegian waters.